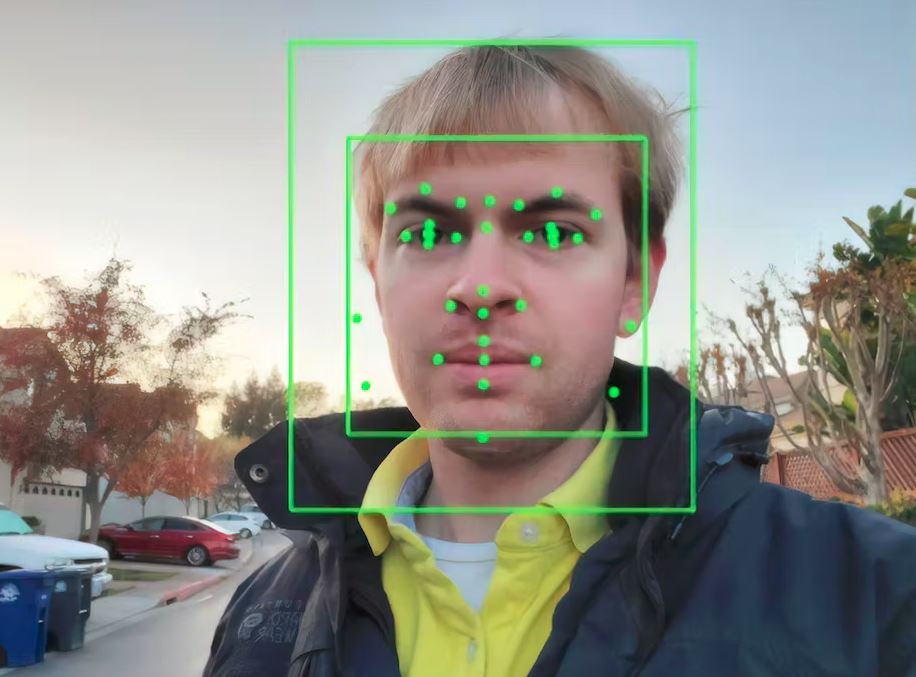

Facial recognition technology is expanding rapidly across Australia. Are our laws keeping pace

Facial recognition technology is increasingly being trialled and deployed around Australia. Queensland and Western Australia are reportedly already using real-time facial recognition through CCTV cameras. 7-Eleven Australia is also deploying facial recognition technology in its 700 stores nationwide for what it says is customer feedback.

And Australian police are reportedly using a facial recognition system that allows them to identify members of the public from online photographs.

Facial recognition technology has a somewhat nefarious reputation in some police states and non-democratic countries. It has been used by the police in China to identify anti-Beijing protesters in Hong Kong and monitor members of the Uighur minority in Xinjiang.

With the spread of this technology in Australia and other democratic countries, there are important questions about the legal implications of scanning, storing and sharing facial images.

Use of technology by public entities

The use of facial recognition technology by immigration authorities (for example, in the channels at airports for people with electronic passports) and police departments is authorised by law and therefore subject to public scrutiny through parliamentary processes.

In a positive sign, the government’s proposed identity matching services laws are currently being scrutinised by a parliamentary committee, which will address concerns over data sharing and the potential for people to be incorrectly identified.

How private operators work

Then there is the use of facial recognition technology by private companies, such as banks, telcos and even 7-Elevens.

Here, the first thing to determine is if the technology is being used on public or private land. A private landowner can do whatever it likes to protect itself, its wares and its occupants so long as it doesn’t break the law (for example, by unlawful restraint or a discriminatory practice).

This would include allowing for the installation and monitoring of staff and visitors through facial recognition cameras.

By contrast, on public land, any decision to deploy such tools must go through a more transparent decision-making process (say, a council meeting) where the public has an opportunity to respond.

This isn’t the case, however, for many “public” properties (such as sports fields, schools, universities, shopping centres and hospitals) that are privately owned or managed. As such, they can be privately secured through the use of guards monitoring CCTV cameras and other technologies.

Facial recognition is not the only surveillance tool available to these private operators. Others include iris and retina scanners, GIS profiling, internet data-mining (which includes “predictive analytics,” that is, building a customer database on the strength of online behaviours), and “neuromarketing” (the use of surveillance tools to capture a consumer’s attributes during purchases).

There’s more. Our technological wizardry also allows the private sector to store and retrieve huge amounts of customer data, including every purchase we make and the price we paid. And the major political parties have compiled extensive private databanks on the makeup of households and likely electoral preferences of their occupants.

Is it any wonder we have started to become a little alarmed by the reach of surveillance and data retention tools in our lives?